Tuesday, November 09, 2010

Monday, November 01, 2010

Hipsterism and Childhood

Fiction Advocate responds to Mark Greif's New York piece with a post about hipsters and their obsession with childhood:

[The] observation – that much of what is “hip” in art today is overly concerned with the stuff of childhood – has been running through my posts on this blog for a while. There was the skepticism I showed for people like Neil Gaiman (Coraline) and Dave Eggers, again, with Spike Jonze (Where the While Things Are) who translate kids’ stories into big movies that are supposed to appeal to adults. . . . Lately it’s been hip for adults to make and consume art that’s essentially for children. I don’t know if the hipster is dead, as Greif says, but I hope this part of hipsterism is dead.

I'm working on a longer response to the Greif essay, but I think this illustrates why hipsters are so hard to define. There is certainly a strain of hipsterism that is concerned with parodying/glorifying things from childhood (think feathered headdresses), but the way in which various groups that we label "hipsters" have been concerned with childhood has changed substantially in the last decade. It's difficult to pinpoint a unified vision.

Meanwhile, within American culture in general, there is an obsession with youth that has grown in the last decade. Youth has been over-inflated for a long time, but the last ten years have seen its value balloon. We've seen the quarter-life crisis, the mainstreaming of twee, the rise of YA books for adults, and the casual office. The once stark line between adults and children has been blurred significantly. We can no longer rely on adults to dress and behave differently from children.

I don't have a larger point to make here, but the obsession with childhood isn't unique to hipsterism. If anything, it seems to be the dominant culture bleeding into subculture.

Monday, October 25, 2010

Monday Roundup

Glenn Greenwald has a good post about the failure of the NYT and WaPo's coverage of the latest Wikileaks story.

According to my friend Brian this book will soon be on sale.

If I understand correctly, this guy is suggesting that the economy sucks because Barney Frank had ACORN thugs force people to buy houses they couldn't afford.

My friend Ashley reviews The Descent.

The cover for Freedom 2 by Emperor Franzen has been revealed.

Friday, October 15, 2010

Friday, September 24, 2010

Friday Videos

Crystal Castles, Celestica

The Hundred in the Hands, "Pigeons"

Friday, May 21, 2010

Hometown News: Where Else Can You Get This Sort of High Quality Racism?

To this day, I maintain an addiction to reading the letters in my hometown newspaper, which, considering that most letters are brimming with unadulterated idiocy, is a little surprising. Still there's something curious about how stupid ostensibly literate people can be.* Take for example this gleaming specimen of critical thinking by Mr. Ricky Tumlin, which starts off thus:

Can anyone please explain to me just exactly what is transpiring in this nation? It is beginning to appear like the years leading up to the rise of Nazi Germany in the early 1930s.

It is no longer fashionable to be patriotic.

Finally! After the better part of century of historical research, psychological and sociological theorizing, political science, and debate, someone has cracked the code: the Nazis just didn't love their country enough to stop killing Jews. What follows is a xenophobic screed against immigrants. The mind reels . . .

* I mean "literate" literally, meaning I'm assuming they didn't dictate their letters to someone else, but who knows?

Wednesday, May 19, 2010

What Makes a Great Jacket?

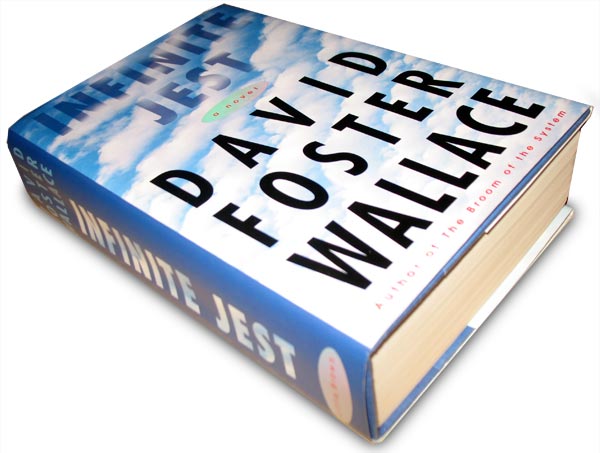

Via my friend/coworker/mentor Keith Hayes, who has three covers in AIGA's latest 50 Books/50 Covers, comes a post by Peter Mendelsund (one of my favorite non-Keith-Hayes designers) about the jacket for Infinite Jest. Mendelsund gives a great summation of what makes a good book cover:

Book jacket design should concern itself with, in my estimation, equal parts enticement ("Come buy this book") and exegesis ("This is what this book is about, more or less.") A good cover doesn't let one category trump the other. A good cover should not resort to cliché in order to accomplish either. But the real key here, in both categories (enticement and exegesis) is the designer's ability to work the sweet-spot between giving-away-the-farm, and deliberate obfuscation.

Book jackets that tell you too much, suck. Book jackets that try to change the subject also suck, and are furthermore, too easy.

Mendelsund goes on to explain why Wallace's suggestion (a design based around a photo of the making of Fritz Lang's Metropolis) would have been a huge mistake (too heavy-handed, too many cultural associations, not really what the book is about). On the other hand . . .

[. . .] a perfectly blue sky... A sky that only an advertiser could have dreamed up- a sky that could have been subsidized...A sky that stands in for satisfaction, but a satisfaction that is almost sinister in its perfection...(and, of course, HUGE type, because, well, that's just what's called for)...I think that was a very elegant solution. It tells you something very important, but leaves everything to the imagination.

What's curious about this cover in particular is that I've never quite thought about it. I judge covers all the time, but this one has always just had a sense of authority to it. I look at it and think, That is the cover for Infinite Jest, excluding in my mind the possibility of any other cover (though, in fact, there are three variations on the same theme in print). Which I suppose is a measure itself of the cover's greatness.

Monday, May 17, 2010

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Military Recruiters and Elena Kagan

Did Elena Kagan ban military recruiters from Harvard Law? According to Peter Beinart, not only did she ban them but she should apologize for what he calls an extreme expression of "national estrangement." Jill Filipovic takes him to task:

I’m not sure if Peter Beinhart is being intentionally intellectually dishonest in this column, or if he just doesn’t actually understand the issues involved in the decision of several law schools to ban military recruiters from campus. He takes Elena Kagan to task for her role, as Dean of Harvard Law School, in “banning” the legal branch of the U.S. military from coming and conducting on-campus interviews. In fact, Kagan didn’t actually ban the military at all — she accommodated them, just not through the Career Services office. And unlike other top law schools, which actually did block the JAG Corps from on-campus recruiting, Kagan allowed JAG recruiters to come to Harvard and interview students through the Harvard Law School Veterans Association, rather than through the career center.

Kagan didn't ban recruiters from the law school campus; she simply didn't allow them to recruit through the Career Services office, a move that Filipovic calls "an even-handed application of an existing policy that applies to all organizations and employers recruiting on campus." Still, they were allowed on campus through the Harvard Law School Veteran's Association.

Beinart argues that "[t]he United States military is not Procter and Gamble. It is not just another employer. It is the institution whose members risk their lives to protect the country." But as Filipovic points out, the recruiters weren't looking for soldiers. They were recruiting for the JAG Corps, which is "different than working in private practice, sure, but it’s not all that different from lawyering at a non-profit organization, or a firm, or as a law clerk, or in another branch of government."

Beinart is a smart commentator, but his hunger for history's narrative power and symbolism seems to lead him to false analogies. Just as Communism isn't a good analogue for Jihadism, Vietnam-era bans on the ROTC aren't good likenesses of Kagan's application of Harvard's anti-discrimination policies. It may make a good story—one that Republicans are eager to exploit—but that's no excuse for ignoring the details at the expense of honesty.

Monday, May 10, 2010

Is Publishing Cannibalizing Itself?

Swelling of the Gland That Makes Stomach-Spit

Wednesday, May 05, 2010

We're All Courtney Love Now

The will to blog is a complicated thing, somewhere between inspiration and compulsion. It can feel almost like a biological impulse. You see something, or an idea occurs to you, and you have to share it with the Internet as soon as possible. What I didn’t realize was that those ideas and that urgency — and the sense of self-importance that made me think anyone would be interested in hearing what went on in my head — could just disappear.

Because I haven't read much of anything on the Gawker network since Ana Marie Cox left for Time and stopped making dick jokes, I missed this now 2-year-old piece by blogger Emily Gould, whom I know mainly from her brief stint at GallyCat. The essay is confessional without being salacious, and it's interesting for how it discusses the relationship between one's personal life and writing. Writing can be away to escape a life of quiet desperation, or it can be an act of stepping over the line into loud, public desperation.

Thursday, April 22, 2010

Real vs. Authentic

The notion of authenticity is practically obsolete, and the idea of realness is just another categorical index, devoid of meaning. When real is gone, then there is no longer a litmus test for that which deviates from it. It's all real because it's all "real." We mined all the gold, and now we're mining the gilded.

The quote above reminded me of a long piece on authenticity that my friend Brian has been urging me to write for months now. Authenticity, it seems, has been wholly replaced by the "real." This is hardly a revelation, but regardless, the culture is still grappling with it. After all, what is "real"? Reality television presents edited and packaged versions of things that really happened, but when producers go about choosing stars who will act in the most salacious way possible, create situations that will assure stars' misbehavior, and then shape it into a narrative, in what sense is it more real and less constructed than fiction? Facts, it seems, are easy to take out of context and manipulate. But even if we grant that the cast members of Jersey Shore are real people doing real things, who in all seriousness could possibly call them authentic?

Archaic though it may sound, I feel strongly that something is lost when we substitute "realness" for "authenticity." Realness seems to have been created by marketers and producers for their financial gain, but is that true, or was it merely co-opted? And if so, authenticity was frequently co-opted too, right? Did realness just get snatched up faster? Part of the reason I've been less than eager to write a piece on authenticity is that I worry that I've failed to properly understand the meaning and value of realness or that I've inflated the meaning of authenticity, which has always been a complicated and often flimsy term.

Still, I wonder, what do teenagers today feel when they read Catcher in the Rye? Does the fact that we've so devalued the authenticity make Holden Caufield's cries against phoniness more urgent, or does it seem like a relic of some past generation that saw value to ideas that simply don't apply or speak to modern life?

Comments welcome.

Wednesday, April 07, 2010

Various

It is, according to my computer's Dashboard, 90 degrees outside. No one else seems to understand why this is great, but if I had my druthers, it would always be 90s degrees outside—at least when it's not raining.

In my office, we have one of those fancy Keurig machines that makes lots of different kinds of coffee, almost all of it awful. Today I was reminded of another office I worked in where we just had a couple large urns and could choose only between regular and decaf. That coffee was also awful, but there was a stronger sense of community in our shared hatred of it.

Georgia politics continue to be more interesting than New York politics.

It's not that I don't like a lot of the new surf-y garage rock that's coming out. It's just that I'd really, really love to hear something innovative and new.

I have a lot of unread books on my shelves, and with the exception of a few things that I like to keep to consult occasionally, I'm considering getting rid of them all and going back to the system I had in college and high school where I would buy a book and then read it right away.

Somehow I keep getting suckered into participating in a book club, even though I have no real interest in it. I'm currently trying to finish Rabbit, Run. Despite the occasional glimmers of lyricism, it's mostly tedious. The suburbs are boring. So, it turns out, is writing about the suburbs.

Thursday, March 18, 2010

If He Died in Memphis, Yeah, That's Be Cool

Friday, March 05, 2010

The Maddest Writer in the USA Has Died

On Monday, Barry Hannah, author of some of favorite short stories, died of a heart attack at his home in Oxford, Mississippi. Truman Capote famously called Hannah "the maddest writer in the USA." When I met him at the Oxford Conference for the Book, shortly after the publication of his brutally gorgeous novel Yonder Stands Your Orphan, he was stoic but generous. At Georgia State, I was an assistant to Pearl McHaney, who interviewed Hannah for Five Points and asked me to transcribe the tape. Inside my copy of High Lonesome, he wrote, "Thanks for the transcript." One of a convention's main speakers, he seemed embarrassed by the attention.

But in his earlier life, Hannah had been a heavy drinker. Stories of his personal life (such as, the time he launched a note at his ex wife's door with a crossbow) were almost as well-known as his writing.

Poet David Bottoms tells a story about Hannah. In the late '80s, when Hannah was paid to give a lecture on writing. I forget the school, but I want to say it was Vanderbilt. The scheduled time for the lecture comes and goes. Hannah is nowhere to be found. His handlers from the English department have lost all sense. They do their best to smooth over the situation and exhort the audience, mostly MFA students, to stay put. Mostly they do.

Hannah finally swaggers into the lecture hall 45 minutes late and trailing a cloud of whiskey perfume. He grabs the lectern to keep himself upright, and says, "Hi--sorry I'm late. I understand the theme of this lecture is 'How to Be a Writer.' The main things you need to be a writer are talent and something to say. After that, the first thing you need is a big dictionary." Hannah takes a step back, turns to the blackboard, and writes, "BIG DICTIONARY."

"It should cost at least $10," says Hannah and turns back to the board. He writes, "AT LEAST $10."

Hannah walks back to the lectern, straightens himself up, and says, "That's all I can tell you. Thanks for having me."

It seems Hannah actually had a good deal more to say about writing, which he taught at Ole Miss for two and a half decades.

I've often tried to push Barry Hannah's writing on my friends, and what I've found is that you either get Hannah or you don't. He often wrote crude things about tasteless, ignorant characters, but he made them real and wrote them with more feeling and energy than any other writer I know. In his story, "Love Too Long," one of Hannah's characters is so heartbroken over the loss of his marriage that he threatens God, saying that if there's not something like his wife in heaven, he will "appear in public places and embarrass the shit out of You screaming that I'm a Christian." All I can say is there better be something like Barry Hannah in heaven.

TRIBUTES

INTERVIEWS

UPDATE: Quote corrected.

Friday, January 22, 2010

Our Robot Masters Will Know How to Clean This Mess Up

The House Democrats seem hellbent on killing health care reform and dragging the entire party down with them, rather than sucking it up and passing the Senate bill. Sure, it's not perfect. Everyone admits that. Still, it's what we've got, and it beats losing for losing's sake. But, hey, don't take my word for it.

Josh Marshall: Pass the fucking Senate bill.

Paul Krugman: Pass the fucking Senate bill.

Steve Bennen: Pass the fucking Senate bill.

Kevin Drum: Pass the fucking Senate bill.

The "Experts" (TPM): Pass the fucking Senate bill.

Jon Cohn: Pass the fucking Senate bill.

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

The Ones That Love Us Least Are the Ones We'll Die to Please

Despite all the sound and fury about a Democrat (who ran a piss poor campaign) losing to some naked Republican in Massachusetts, the Democrats still hold solid majorities in both chambers and control the executive branch. So why are they dead set on letting the Republicans run right over them? I don't understand the logic of forfeiting health care reform, when it only proves the Republican claim that Democrats won't even fight for what they believe in. If they keep this strategy, they're going to lose big in the next election cycle. It's not just going to be a matter of one seat. Moreover, they deserve to lose. It would be only a minor exaggeration to say that members of my own family won't be around to vote them back into power if they drop the ball on health care reform. It may sound melodramatic, but it's true.

What's particularly galling is that no one seems willing to take charge. The most obvious choice would be the president, but he's punted at every opportunity. TPM: Dem talking points: "It is mathematically impossible for Democrats to pass legislation on our own." Uh huh, sure. TPM: Hill staffer: "I believe President Clinton provided some crucial insight when he said, 'people would rather be with someone who is strong and wrong than weak and right.' It's not that people are uninterested in who's right or wrong, it's that people will only follow leaders who seem to actually believe in what they are doing. Democrats have missed this essential fact." Kevin Drum: "[G]oing back to the drawing board and trying to pass a few little piecemeal reforms is suicidal. It's one of the worst ideas I've ever heard. One of the big problems with healthcare reform is that the public is sick of the process. The last thing they want is for Congress to spend several more months flailing around on it."Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Friday, January 15, 2010

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

The Healing Power of Television

Over at Stereogum, songwriter and memoirist Julianna Hatfield has a very persuasive op-ed about the the new season of VH1's Celebrity Rehab, a show she describes as follows:

The camera follows you around, inflating your importance in and to the world, glorifying and broadcasting your troubles over the airwaves into millions of peoples' homes. All this does is to perpetuate the fame and self-involvement that can really mess with a person's -- especially an addict's -- head.

She goes on to express concern that, far from helping the stars, the show is actually making them worse.

A 12-step program won't work without humility and humility is not possible with lights and cameras and microphones trained on you, following you around, inflating your importance. And real community and support is not possible on a TV set. The aims of a TV production are in direct opposition to the goals of rehab.

Is Celebrity Rehab helping or hindering the people taking part in the show? They are, after all, being given drug rehabilitation treatment and getting paid for it. The fact remains, however, that they're on the show precisely because they're addicts. Regardless of the apparent encouragement to get sober, the shows producers are rewarding them with attention and money for doing just the opposite. On the one hand, it's hard to sympathize with self-obsessed drug addicts bent on getting another stab at fame. On the other, aren't they just doing what they're told?

This, of course, raises another question: are we, as viewers, complicit in the producers' manipulation of the shows stars? Is watching bad behavior tacit approval? By watching them, aren't we the ones rewarding them with the attention they crave?

Hatfield ends her essay by asking, "When [Dr. Drew Pinsky] listens to the addicts tell their terrible sorrowful grotesque stories the look on his face is genuinely sympathetic and caring, I think. It's real, I think. It's real. Is it real? Is it real?" There's something plaintive in her question. Obviously, Pinsky is being paid for his participation in the show, but of course, all professional therapists are paid for the services they deliver. Hatfield isn't so much asking whether Pinsky cares for the show's stars as patients as re-asking the questions she raised earlier: Can shows like Celebrity Rehab make people better? Are we, as viewers, helping? It's a comforting thought, that we can help people just by watching television, and Hatfield wants to believe it, even as she's explained that it's plainly untrue. Count me, likewise, among the skeptics.

Friday, January 08, 2010

Wednesday, January 06, 2010

Prose Television

The Fiction Advocate has a nice little run-down of David Foster Wallace's 1990 essay, "E Unibus Pluram."

Brian's particularly interest in Wallace's take-down of what he (Wallace) calls "witty, erudite, extremely high-quality prose television." Brian writes, "If he were still alive, I would love to hear him pick apart the layers of irony in a show like 30 Rock, or a writer like Tao Lin."

I'm curious too, but I think it's worth pointing out just how self-conscious the essay is. Wallace rarely commented on his peers and only occassionally wrote about his forebears, but he was extremely aware of the weaknesses of his own writing, which he worried was shallow, cute, and primarily concerned with making himself look good rather than revealing deep truths. When he talks about "prose television," he's almost certainly referring to his own early writing, which explains the progression of his writing from the neurotic slapstick of The Broom of the System to more interior, increasingly discursive narratives like "Mr. Squishy."